Carnaval and the last weeks of research

Carnaval has come and gone and Olinda has returned to its normal routines. The weeks leading up to it had more and more festivities until finally for almost a week straight there was almost non-stop music, revelry, irreverance, and the resulting joy and heartache of Brazil magnified many times over. The joy is abundantly obvious: the dancing, playing, loving, living for and in the moment. The pain more hidden but still there, fights in the crowd, the newspapers with headlines about police abusing and killing suspects they detained. Carnaval is a ritual (or series of rituals) that seems to speak volumes about not only its specific place in the lives of Brazilians, but of how people here construct identities and view themselves, their region and country and its imagined characteristics.

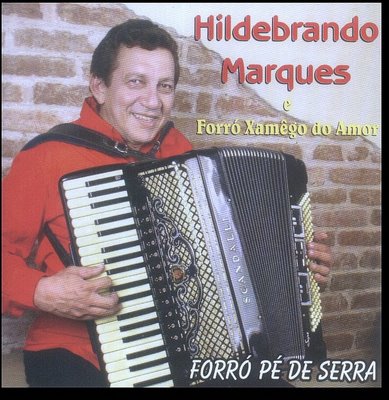

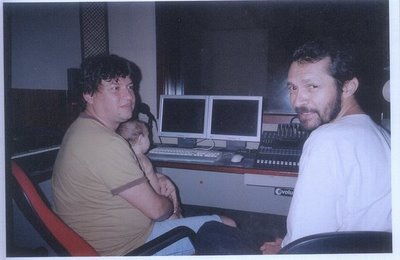

My research has been steadily moving forward as I have been talking with and interviewing various forró musicians. I still have hours of recorded conversations that I have to pour over and transribe, but I have been noticing various themes, viewpoints, and dialogues appearing again and again. One of these is the clash between what is perceived as "traditional" and what is construed as "modern" and how values are attatched to these notions. I have been fortunate to be able to interview a variety of musicians (young, old, professional, semi-professional, male, female) that have had differing opinions and ideas about how they view connections to what many refer to in terms of "roots" (raizes), or "blood" (sangue) and their music. Many have concurred that they have choosen to play forró (and other genres associated with this area) because they feel that it is an important part of their identity as Pernambucans and Northeasterners. A common feeling expressed has been a critique of mass media here and its perceived (mis)treatment of local culture. At the same time, there are strong (and differing) feelings and ideas of how to both preserve local cultural expressions while negotiating boundaries between these and other (outside) influences. Many of the musicians have welcomed some changes, while balking at others, differentiating between innovation and commercialization of their music.

Issues of social class have been also appearing with many informants telling me that forró was essentially considered of the poor and uneducated, and suffered because of this preconception for many years. Opinions have differed about when and why a change has come about, but all have concurred that it is no longer the case. Many have given a time period of significant change in attitudes about the music from the mid 80´s to the early 90´s. This was a time of great change in Brazil, especially politically as the transition was made from a military dictatorship to a democracy. Informants have told me that from the 90´s there has been a change in the values that young people here have given to music and other cultural expressions produced locally. At the same time, it has been repeatedly commented that this has been something that has been hindered by lack of support from radio, television and other forms of mass media, as well as lingering notions among large segments of the population that externally produced forms, styles, and creations have more value .

Another interesting point that has been called to my attention frequently is that many of my informants are also involved in research themselves. This takes the form of gathering information about what they consider to be their own cultural backgrounds, heritage, or "roots" that take form in sounds, ideas, lyrics, poetry, instruments, genres, behaviors, and material items.

In other news unrelated to my research I have had two contacts with the local military police in the past week. As I was riding with my friend on his motorcycle on the university campus to return a book we were stopped by three cops also on bikes. For some reason they seemed to be focused on me more than him and when I got off the bike one of them barked at me to keep my hands on my head. As I turned around to explain that I didn´t have anything on me I saw that one of them had his gun pointed at me. When they didn´t find a single machine gun or pistol on me (luckily I had left all my customary weapons of medium destruction at home) we were allowed to explain that I was returning a book. My friend and I entered the uni wondering how things were on campus during the military dictatorship here (brought to Brazil with the help of our good friends at the CIA).

The second incident was yesterday as I borrowed my friend´s bike to do some shopping for breakfast. Returning from the bakery I was randomly stopped (they call it a 'blitz' here) and when the two cops saw that the registration had expired the day before the problems started. They then told me that I needed a translation of my California driver´s license. I pretended not to speak Portuguese (dealing with the police here it is usually better to be the ignorant gringo)and repeatedly said in Portanglish that my friend lived close by. I finally convinced them to follow me to our house where the owner had them come in for some juice. Finally they were convinced that justice would be best served with 20 reais. It seems as there is a strong environmental movement here among the police as well as they said there was no need for any paperwork or receit (thus saving valuable paper).

Stay tuned for the next post as I will discuss some more of my research and findings.